America’s Forgotten Warriors: Why the Hmong Deserve to Be Recognized as U.S. Veterans

Exposing the truth behind MN Senator Andrew Lang’s comments and why America must finally honor its Hmong allies from the Secret War.

Minnesota State Senator Andrew Lang’s recent comments dismissing Hmong fighters as “mercenaries” and denying their claim to veteran status are not only historically inaccurate—they’re morally indefensible. Speaking about a bill that would grant state-level veteran recognition to Hmong soldiers who served in the CIA’s Secret War in Laos, Lang claimed, “They’re not veterans… They worked as mercenaries for the CIA… They never wore a U.S. uniform” (Willmar Radio, 2025).

His remarks reflect a troubling misunderstanding of what it means to serve—and who gets to be honored for that service. Let’s set the record straight.

The Hmong Fought for America, Not for Money

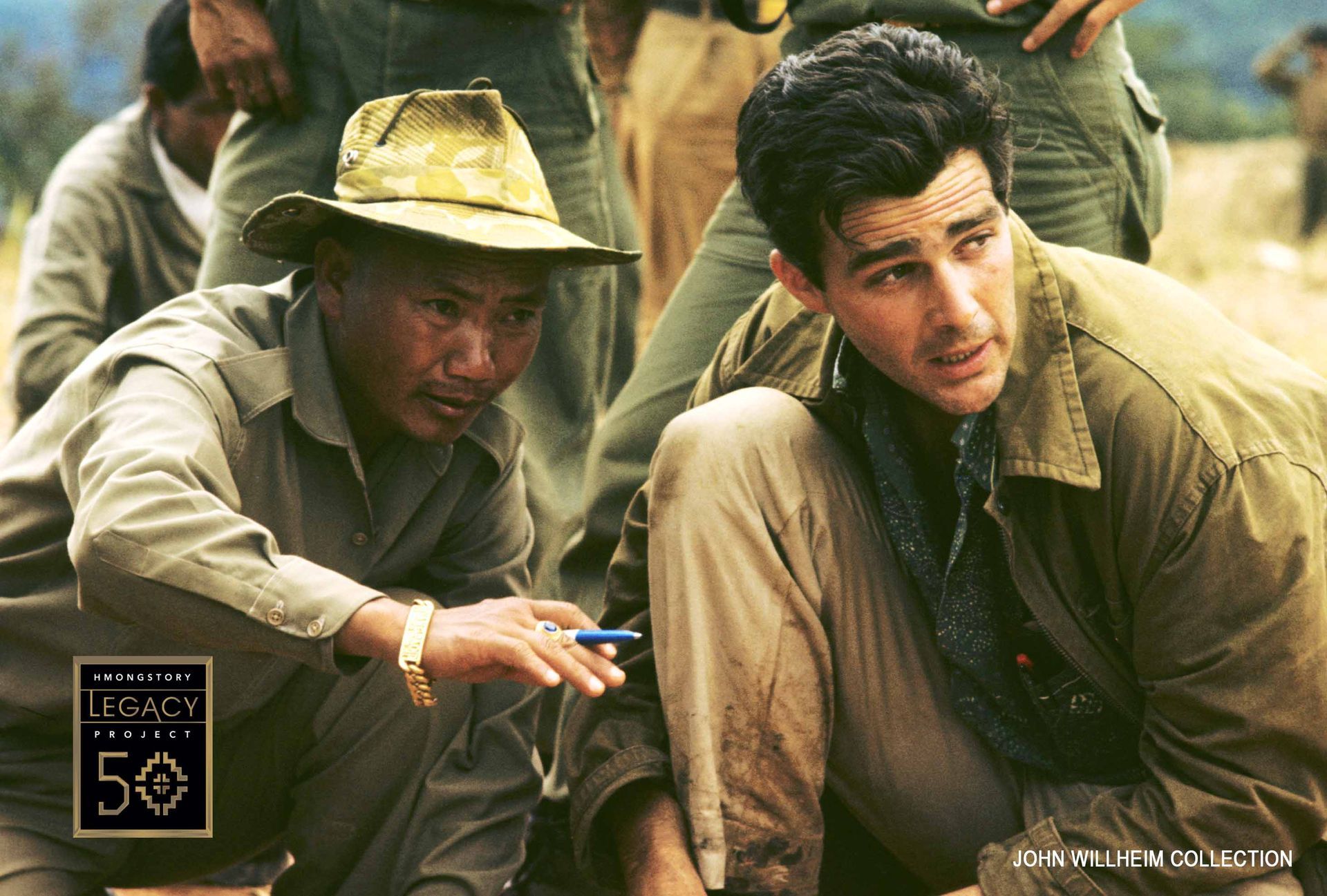

To call the Hmong “mercenaries” is to completely ignore the reality of their sacrifice. The CIA trained, armed, and commanded tens of thousands of Hmong fighters during the 1960s and ’70s to help stop North Vietnamese forces in Laos. These men weren’t chasing profit—they were defending their homes, villages, and families from communist aggression, all while carrying out U.S. missions.

Their work was dangerous, strategic, and vital. They rescued downed American pilots. They fought on the front lines of a war the U.S. government didn’t want the public to know about. They paid for that loyalty with their lives.

Uniform or Not, Their Service Was Real

Senator Lang argues that because the Hmong didn’t wear a U.S. uniform or swear an oath to the Constitution, they shouldn't be considered veterans. That’s bureaucratic nonsense. The measure of a veteran is not the uniform—it’s the service.

History is full of examples of foreign nationals who fought under U.S. command and were later recognized:

- Filipino soldiers in World War II fought under General Douglas MacArthur without wearing U.S. uniforms or taking formal oaths. Decades later, they were granted veteran recognition and benefits by Congress.

- Montagnards, another indigenous group in Vietnam, also fought alongside U.S. forces. Though few received formal status, many Americans who served with them have lobbied for their recognition.

- Korean Augmentees to the U.S. Army (KATUSA) have served integrated into American military units since the Korean War. Though not U.S. citizens, their service is honored and recorded because they fought under American command.

What all these groups share with the Hmong is this: they put their lives on the line for American military objectives, followed U.S. orders, and fought beside U.S. personnel. The Hmong sacrificed more than most. Over 20,000 Hmong soldiers were killed in combat, 50,000 civilians lost their lives, and 120,000 were displaced—all in service of a war America directed but never officially acknowledged.

If anything, their loyalty under covert, high-risk conditions deserves more recognition—not less.

Recognition Isn’t Political—It’s Moral

This isn’t a new political trend. The Hmong community has been asking for recognition for decades. What’s changed now is urgency. As reported by

AsAmNews, fewer than 1,000 Hmong veterans remain alive in Minnesota. They are aging, in need of care, and still waiting for the basic dignity that recognition would bring.

The Minnesota bill wouldn’t even grant full federal VA benefits. It would simply allow aging Hmong veterans access to state veterans’ homes, burial honors, and other modest forms of support. This is the bare minimum for men who gave everything for a war the U.S. fought in the shadows.

Many American Veterans Stand With the Hmong

Senator Lang claimed some Vietnam veterans asked him to oppose this bill. But he does not speak for all veterans.

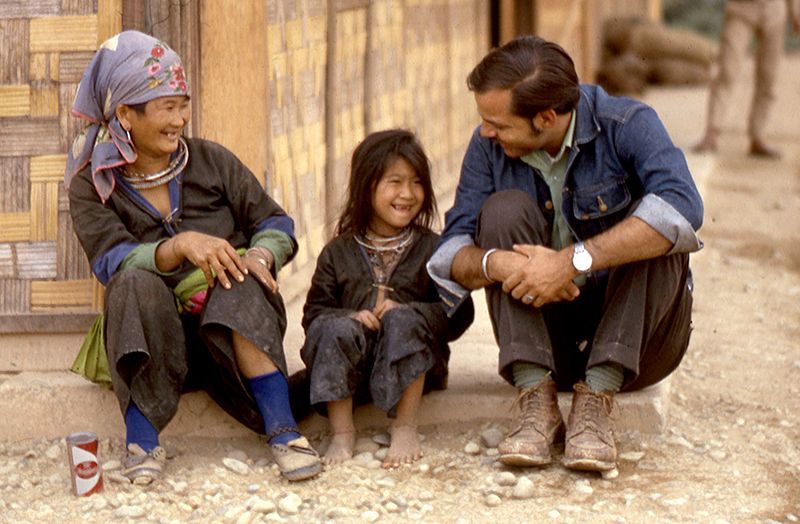

In fact, many American soldiers who served in Southeast Asia have publicly supported Hmong recognition. Why? Because they know what the Hmong did. U.S. pilots owe their lives to Hmong rescue teams. American soldiers benefitted from Hmong intelligence and frontline combat efforts. Veterans who understand the war know the truth: the Hmong earned their place.

Comparing the Hmong to Shia Militias Is Offensive

Senator Lang compared Hmong fighters to Iraqi Shia militias—groups that at times fought against American forces. This is not just inaccurate—it’s insulting. The Hmong never turned against America. They stayed loyal for over a decade, fought to the very end, and were hunted and killed when the U.S. pulled out of Laos in 1975.

Even then, many fled to the U.S. and rebuilt their lives as loyal citizens. Their children now serve in the U.S. military, run businesses, and contribute to American society. They are not enemies. They are part of the American story.

Final Word: It’s Time to Honor the Promise

America asked the Hmong to fight. The Hmong delivered. When the war ended, we abandoned them. The least we can do now is offer them the recognition and respect they’ve earned.

Senator Lang’s statements reflect a narrow view of military service and an outdated understanding of what it means to be a veteran. This isn’t about uniforms or legal status. It’s about sacrifice. It’s about truth. And it’s about keeping our word.

If America is to have any honor, it must honor the Hmong.

Sources

- Willmar Radio. (2025, April 10). Lang says Hmong fighters were mercenaries, not soldiers. Link

- Lee, T. (2025, April 10). Hmong American soldiers from Secret War in Laos seek recognition, benefits. AsAmNews. Link

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2009). Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund.

- MacDicken, K. (2015). The Montagnards and America’s Broken Promises. Foreign Policy.

- U.S. Army. (2021). KATUSA Program Overview. U.S. Army Garrison-Humphreys.