The Hmong living in Laos primarily practiced Slash & Burn Farming. It is a very labor-intensive method involving manual labor to chop and clear a whole mountain side, burning the trees and then the ashes become the fertilizer without much developed irrigation systems. The Hmong grew hill rice which yields much less harvests than lowland rice. After two or three years when the fields are no longer productive, they must find richer areas to grow crops. The people from the village pack up and move to another area to rebuild their village and grow crops on more fertile land. This would require them to travel a short distance to the next region to build a new village. Sometimes, they would need to travel further if the neighboring areas were not appealing to them or occupied by others. However, it is uncommon for a whole village to pack up and leave altogether. They relocated independently from family to family, and it is common for a household to remain in one location for 10 to 15 years. Village Life Crops Three of the major crops that the Hmong cultivated were rice, corn, and opium. They learned to cultivate these crops after living in China. Corn and rice were planted and harvested during different seasons: corn was harvested during the rainy season and rice was harvested during the dry season. This allowed for more productive use of their land. Thereby providing a reliable supply of food. If a family did not produce a good harvest of rice in one year, they will have security of harvesting the corn crop. This meant that the Hmong worked year-round and were able to schedule New Year rituals and festivities during the very last days of December. Opium, however, was historically harvested in China where the Hmong learned how to cultivate the crop. The mass production of opium occurred in Laos after the French imposed a new tax law in Laos, which required the Hmong to use opium as a tax payment. Animal Husbandry Livestock were a valued commodity for the Hmong. Horses, cattle, and goats were kept outside in their stables; pigs and chickens in their cribs; and dogs were allowed to roam freely. Sometimes chickens were raised in an open space, which allowed them to roam. A cock was usually tied near the house where he served as an alarm clock. The Hmong also hunted animals in the surrounding forest for food and for game. They used crossbows and traps before being introduced to the musket guns. Those who had money could afford guns to hunt. Boys would learn to hunt and trap squirrels, rats, and birds. As men, they hunt and trap deer, wild boars, bears, and tigers. A Typical Annual Agricultural Schedule January and February: Prepare farming tools to clear the fields MARCH AND APRIL: Clear the fields for burning in May MAY: Right before the rainy season in the summer, the fields are burned, and the ashes become fertilizer for the coming planting season; grains are prepared while the fields are burned so they can plant in the summer and be ready for harvesting in the late fall SUMMER: Planting season FALL: Harvesting season. This is the most critical and demanding time of year with so much to do. Harvest must be completed by the beginning of December to ensure the family can survive the following year. DECEMBER: Harvesting is complete and the end of the month is reserved for New Year rituals and festivities

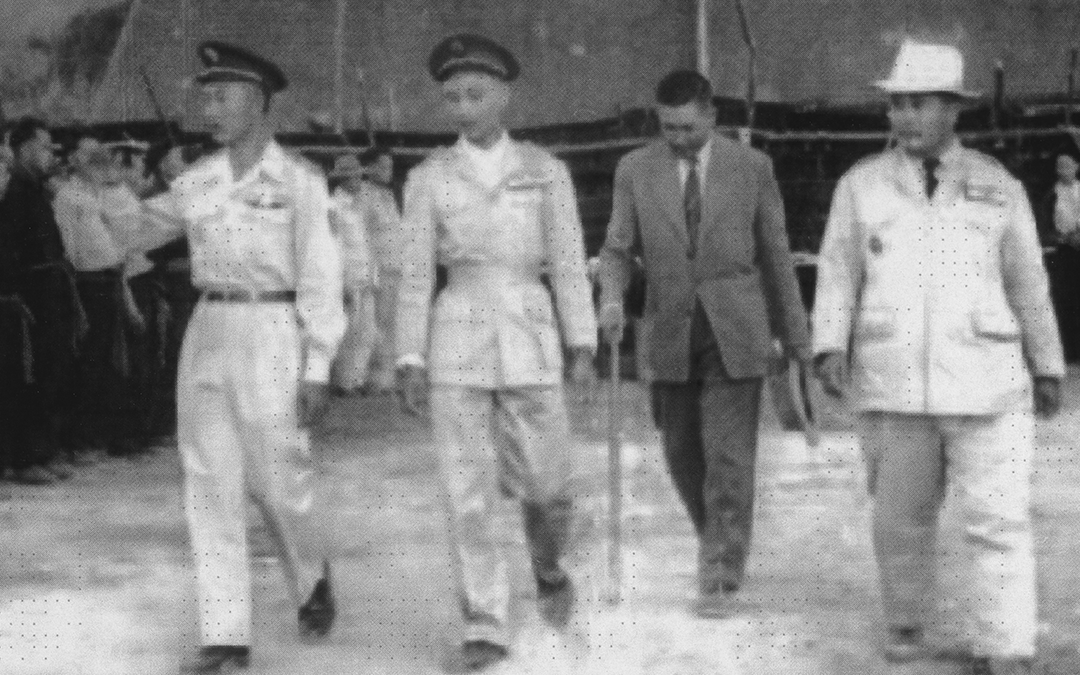

After the defeat of Japan in WW II, Japanese forces in Indochina surrendered, and nationalist movements rose to resist the return of French colonialism. In Laos, three brother princes, Phetsarath, Souvanna Phouma, and Souphanouvong, headed the Lao Issara (Free Laos) movement, which demandedfull Lao independence. Lo Fay Dang, Touby Lyfoung’s uncle on his mother’s side and one-time competitor for the title of Tasseng of Keng Khuai, immediately joined the Lao Issara. Although, Touby Lyfoung, along with King Sisavang Vong, felt that Laos needed a gradual transition to independence, under the protection of France. They felt that the achievement of an abrupt independence would leave Laos in a weak state, easy to be taken over by stronger neighbors such as Thailand or Vietnam. In October 1945, the Lao Issara formed a new government and attempted to dismiss the king. Prince Souphanouvong was appointed minister of defense. He formed a new army with help from the Vietminh and Chinese army. However, the Vietminh had to fight their own war with the French and the Chinese army had to retreat back to China, leaving the Lao Issara army alone to fight the French. In December 1945, the Lao Issara government in Vientiane sent an army to take over Luang Prabang and depose the king. It was supposed to join up with a Vietminh force coming from Vietnam. Before the two armies could join forces, Touby Lyfoung and the Hmong, Royalist Lao troops, and the French defeated the Vietminh force. Then they defeated the Lao Issara force, saving Luang Prabang and the king. By April 1946, the French had retaken control of Vientiane and Luang Prabang, and the Lao Issara had fled to exile in Thailand. In 1949, the Lao Issara split between Communists and non-Communists, and it was disbanded. The Communist faction, under Prince Souphanouvong, became part of the Pathet Lao (Lao Nation), close allies with the Vietminh of North Vietnam. The Pathet Lao was a subsidiary of the Vietminh. Its army was trained, armed, and led by North Vietnamese army officers. It fought side by side with North Vietnamese soldiers. In 1953, the French was defeated at Dien Bien Phu. Pathet Lao and Vietminh forces started moving into Laos to fight the French and Royal Lao government. These forces took control of eastern Laos and gained a foothold in the country. In the Geneva Accord of 1954, foreign forces were required to leave Laos, but the Vietminh never did. In 1957, a coalition government was formed, including the Pathet Lao, but it fell apart in 1959. For the next decade and a half, the Vietminh and Pathet Lao would go on to sign two more Geneva Agreements that they would break and the Pathet Lao would join two more failed Laotian coalition governments. Laos was too important for the Vietminh to let go, and the Pathet Lao was not interested in sharing the governing of Laos with anyone else. SOURCE: Lyfoung, Touby with Dr. Touxa Lyfoung. Touby Lyfoung: An authentic account of the life of a Hmong man in the troubled land of Laos.

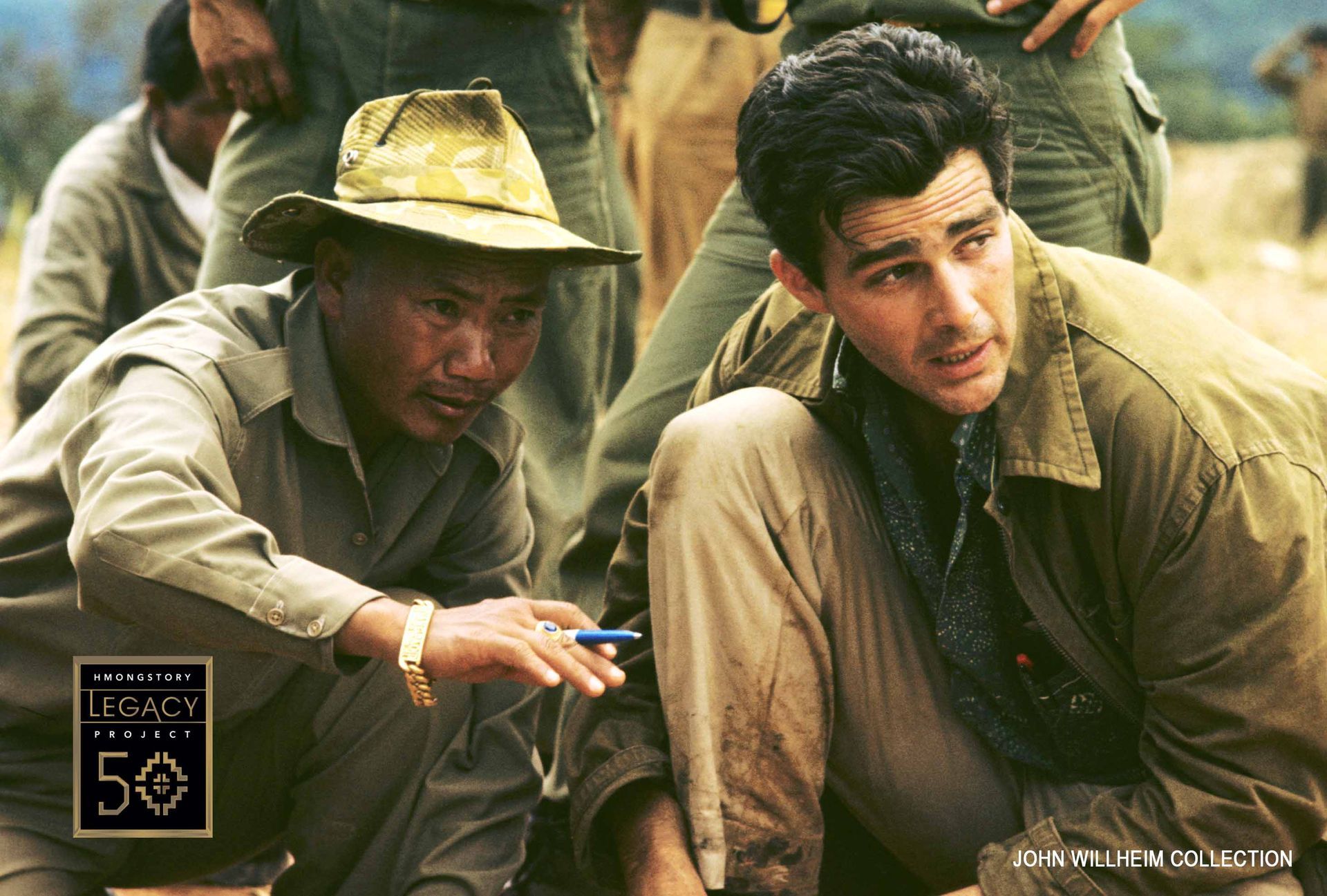

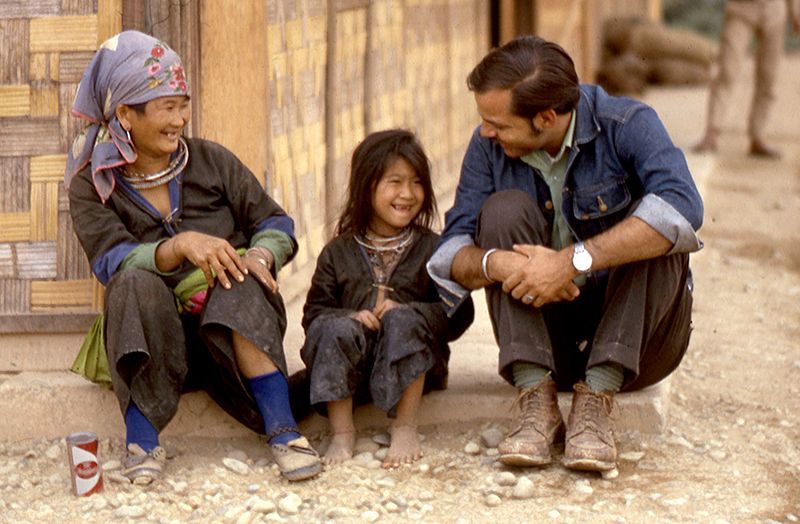

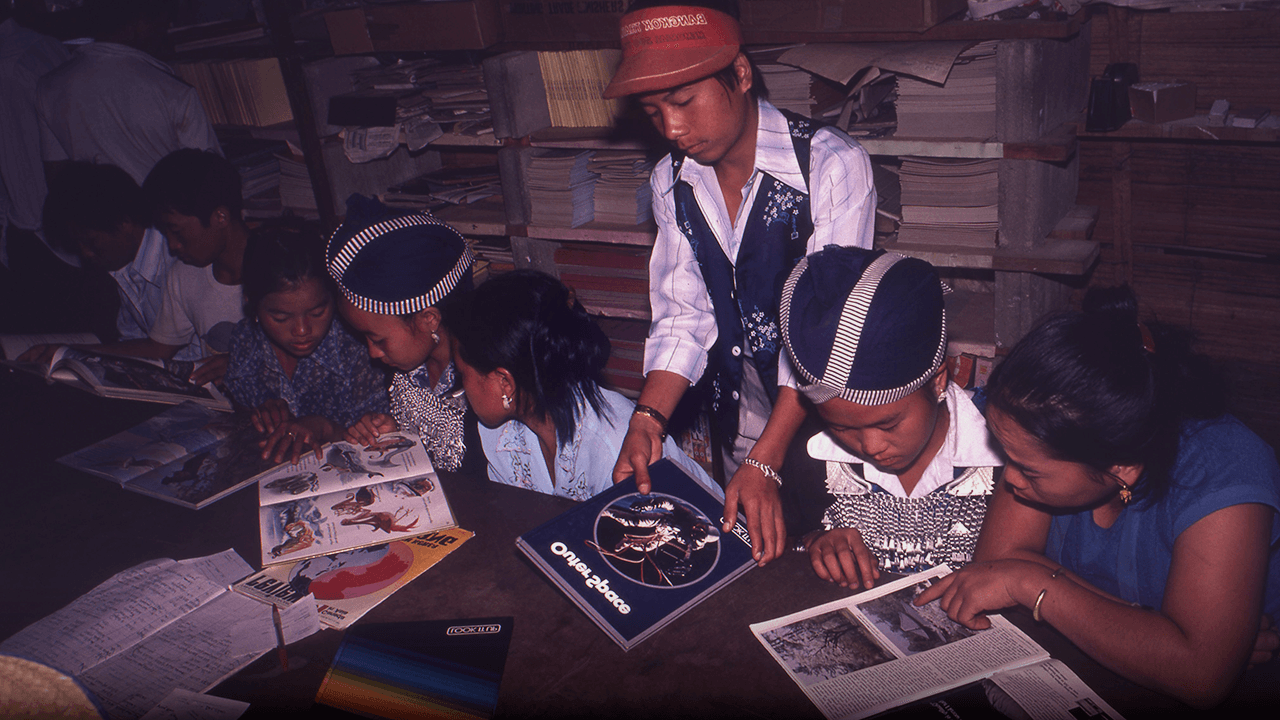

My Hmong brothers and sisters, I know sometimes you feel powerless, don’t know what to do… You’re stuck in place with nowhere to go. Then I want you to remember this word: MOMENTUM. Our parents and grandparents were stuck on the mountains of Laos, subsisting on daily labors, backbreaking each day in the fields only to feed the family for the night, day after day, month after month, year after year. Then the U.S. and Thai governments saw us and said: Look how strong, how enduring they are, yet so ignorant of the world. We’ll use them as a sword to fight our war, as a shield to deflect our enemy’s weapons, as a wall to halt our enemy’s advance. We’ll call this: Operation Momentum. So we were conscripted, taught to read and write, trained to fight and fly, and we have been gaining MOMENTUM ever since, like a rock rolling down a mountain slope, like a river surging toward the sea… And here we are, from preliterate mountain tribespeople to nurses, doctors, teachers, superintendents, lawyers, legislators, builders, architects, actors, producers, and yes...poets, writers… in the mere span of fifty years. That’s MOMENTUM! So when you’re stuck, remember you are M O M E N T U M…

During World War II, Japanese soldiers who occupied Laos and Indochina let the French administrators and soldiers rule as they had for fifty years. These local French administrators were working for the French government of Marshal Petain, which was a puppet government of Japan’s ally, Germany. Japanese and French lived side by side until March 1945. On March 4th, French resistance soldiers under General De Gaulle flew from their base in India, parachuted into Laos, and contacted Hmong leader Touby Lyfoung. Touby Lyfoung was Tasseng of Keng Khuai, who oversaw sixty villages in Nong Het district. The French troops requested Hmong guides to help them in their effort to launch guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. They told him there were French commandos like them being inserted throughout Indochina to take it back from the Japanese. Touby Lyfoung agreed and provided Hmong men as guides for the French soldiers. On March 9th, Japanese troops took control over the country and tried to arrest and disarm all French administrators and soldiers. At the same time, there were nationalist uprisings throughout Indochina. In Laos, the Lao Issara (Free Laos) movement rose to resist French colonialism and declared Lao independence. At Nong Het, the local French commander destroyed his own supplies, hid his wife and children with local Hmong, and fled into the jungle to join the French commandos. On March 24th, three hundred Japanese soldiers passed through Nong Het, leaving thirty soldiers to man the Nong Het post, before continuing to the Plain of Jars. In April, Touby Lyfoung was arrested by the local Japanese commander and was asked if he had hidden the French weapons, supplies, and money. After three days of questioning, he was released, but he realized that he was in danger, so he fled with his family and relatives into the jungle. While Touby Lyfoung was hiding in the jungle, Lo Fay Dang, Touby Lyfoung’s uncle and one-time competitor for Tasseng of Keng Khuai, was put in charge at Nong Het. Lo Fay Dang did not like the French and was well-connected to the Japanese. When Touby Lyfoung heard that Lo Fay Dang’s men and Japanese soldiers were torturing his relatives for information, he fled even deeper into the jungle, where he and his family remained for four months. Lyfoung, Touby with Dr. Touxa Lyfoung. Touby Lyfoung: An authentic account of the life of a Hmong man in the troubled land of Laos. Piece written by: Soul Vang

THE POLITICS OF OPIUM For the Hmong, the main aim of poppy cultivation has always been commercial. It is the ideal crop that could be sold for cash, especially silver bars and coins in the old days before paper money came into use. How much yield a grower gets each year depends on the quality of the soil, the size and altitude of the field, and how many workers a household has. Apart from cash, opium is exchanged for necessities such as salt and clothing materials. Some is used for smoking by village addicts, but their number is usually very low due to strong social stigma against opium addiction in Hmong society. Sometimes, it is used as poison to commit suicide, especially by Hmong women, but it is never used as part of Hmong rituals like rice or domestic animals. Until the 1950’s before the advent of cars and roads, which made it possible to go to markets at the nearest towns, Chinese trading caravans used to sell goods to remote Hmong villages, using horses as transport. The Hmong, in turn, sold or exchanged their opium to these caravanners so that growers had no need to travel anywhere to sell their opium. For this reason, Hmong who migrated to Laos from China often settled along these trading routes. In fact, there are stories about young Hmong men (e.g. Touby Lyfoung’s grand-father) who migrated south, while serving as porters for Chinese traders. After making Laos a “protectorate” of France in October 1893, the French levied a head tax (se taub hau neeg) on all male residents of the country, ages between 19 and 60, to fund operations. For the Lao in the lowlands, this tax was set at 2 piastres (2 txiaj kis) per person per year (payable in cash or kind e.g. domestic animals), along with 20 days of corvee or free labour given to the authorities. For the Khamu, Hmong and other minorities, it was one piaster and 10 days of free labour. In 1896, this tax was increased and payable only in cash. The problem for the Hmong was that Lao local officials/princes also collected their own taxes. In addition, Hmong chiefs who acted as tax collectors for the Lao and French authorities also levied their own tax and corvee labour to get their own money and to have village people doing farm work for them. All these different levels of taxation and corruption greatly inflated the amount of taxes people had to pay each year. Many of the poorer Hmong could not pay, and there are stories of some having to sell or pawn children to richer Hmong to borrow money for their tax obligations. Due to this financial burden, the Hmong had to increase their opium cultivation as the only means to get money to pay for their family needs and their taxes. Even those who previously did not grow opium now had to do it. The impact of this severe official taxation is that the Hmong rose up in rebellion known as RogVwm or “Mad Men’s War” under the leadership of Pachay Vue (Paj Cai Vwj). Aided by Hmong messianic beliefs, the rebellion lasted from 1918 to 1921 – starting first in Vietnam and quickly spreading to all of northern Laos. The French had to bring colonial troops from other parts of Indochina to put it down. Today, Pachay is still celebrated by the Hmong of Laos and Vietnam as a revolutionary hero. In 1947, the first Hmong deputy elected from Xieng Khouang to the Lao National Assembly in Vientiane, Mr Toulia Lyfoung, lobbied against this head tax and it was abolished, thus finally releasing the Hmong and other Lao citizens of this heavy burden. HOW THE POPPY IS GROWN In the traditional Hmong economy, no family would grow only one kind of crop as this would not meet all the family’s needs. Rice grows best in lower altitudes, so rice fields are often located lower down the mountain slope, away from maize and poppy fields. If a family grows all three major crops, then rice, maize and opium would be integrated into the annual farming cycle. Each family would give equal attention to them, although, the labor requirement may differ from one crop to another. Rice and opium has been found to need the same labor intensity (about 220 mandays per hectare), with maize about one two thirds less (80 mandays/hectare). Maize (or corn) and poppy usually share the same field as both are suited for the same soil, altitude and weather conditions, with maize being grown first. All fields are worked by hands as they are often too steep and growers have no machinery to use. The scheduling of labour for each crop depends on the weather and how many workers are available. Maize fields (teb pob kws) are cleared (luaj teb) in January and February, followed by burning (hlawv teb) in March. Maize planting (cog pob kws) takes place in April, and weeding (dob nroj) in May. The first corn cobs are harvested (ntais pob kws) in June-July, and by September all harvesting should be completed. August sees the preparation of the maize fields for poppy growing, starting with hoeing (faus teb yeeb) – turning up every inch of the soil manually with a hoe (hlau) and burying the dry maize stalks and weeds under. Early sowing of the poppy seeds (tseb yeeb) begins in September and should finish by October, a time when the Hmong are also busy harvesting rice. November and December are spent weeding (dob yeeb) the poppy seedlings and young plants, a time when the Hmong also celebrate the New Year. Using a three-bladed small knife (riam yeeb), workers will tap the opium pods (hlais yeeb) and collect their sap (sau yeeb) with a scraping blade (duav yeeb) in January and February. Once collected, the sap (yeeb nyoos) from all the tappings is put together in a small container and allowed to dry. The year’s harvest is then wrapped in bamboo papers to be stored for safe-keeping and sale. The process completes with growers collecting poppy seeds (muab noob yeeb) in March to be used for the following year, and the next cycle of cultivation starts all over once more. D. Feingold, “Opium and Politics in Laos”, in N. S. Adams and A. W. McCoy eds. Laos: War and Revolution (NY: Harper Colophon Books, 1970), p. 329. Although they grow the drug, less than 10% of the Hmong are addicted to opium,. See J. Westermeyer, “Use of Alcohol and Opium by the Meo of Laos”, American Journal of Psychiatry, 1971, 127 (8), p.1021. G. Evans, A Short History of Laos, the Land in Between (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2002), p. 46. M. Stuart-Fox, A History of Laos (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 32

After long months of wandering without knowing how the river will unfold for them, they’re people beneath a moon before the river preparing to settle for the night and to pray to their ancestors for a safe crossing, like a crossing over a bridge into the clouds. They ask in their prayers that the river will be one which the water will open up to the land and let them pass without fear of the unknown dead. Their journey is like a journey towards the sun; often the way towards it is not the way back to the home they long for or remember nor will it be a way to return to the days in which they could sleep quietly before smelling the sacred and delicious first - harvested rice. They know the way they have come will be a way of memories etching deep into their minds and hearts. Before they rest to watch the silence of the river reflected above in the night sky, they would tell tales to quiet their children. They would tell, as if there were no war, the tale of a goddess who journeys to the moon searching for a pond in which her lover was held captive. But the children grow weary, maybe they’re themselves captives, of the long travel and soon fall asleep, before the story ends. But of all these tales they have not forgotten to include those who would shoot them for the silver bars they wear around their waists. Some of them might not be able to hear of the tale about themselves meeting the river: for they do not know if their ancestral spirits will take them across the river through a bridge made by the river. This poem taken from the chapbook Where the Torches Are Burning, published by Swan Scythe Press. © by Pos L. Moua. For use by permission from author.