Opium and The Hmong

THE POLITICS OF OPIUM

For the Hmong, the main aim of poppy cultivation has always been commercial. It is the ideal crop that could be sold for cash, especially silver bars and coins in the old days before paper money came into use. How much yield a grower gets each year depends on the quality of the soil, the size and altitude of the field, and how many workers a household has. Apart from cash, opium is exchanged for necessities such as salt and clothing materials. Some is used for smoking by village addicts, but their number is usually very low due to strong social stigma against opium addiction in Hmong society. Sometimes, it is used as poison to commit suicide, especially by Hmong women, but it is never used as part of Hmong rituals like rice or domestic animals.

Until the 1950’s before the advent of cars and roads, which made it possible to go to markets at the nearest towns, Chinese trading caravans used to sell goods to remote Hmong villages, using horses as transport. The Hmong, in turn, sold or exchanged their opium to these caravanners so that growers had no need to travel anywhere to sell their opium. For this reason, Hmong who migrated to Laos from China often settled along these trading routes. In fact, there are stories about young Hmong men (e.g. Touby Lyfoung’s grand-father) who migrated south, while serving as porters for Chinese traders. After making Laos a “protectorate” of France in October 1893, the French levied a head tax (se taub hau neeg) on all male residents of the country, ages between 19 and 60, to fund operations. For the Lao in the lowlands, this tax was set at 2 piastres (2 txiaj kis) per person per year (payable in cash or kind e.g. domestic animals), along with 20 days of corvee or free labour given to the authorities. For the Khamu, Hmong and other minorities, it was one piaster and 10 days of free labour. In 1896, this tax was increased and payable only in cash.

The problem for the Hmong was that Lao local officials/princes also collected their own taxes. In addition, Hmong chiefs who acted as tax collectors for the Lao and French authorities also levied their own tax and corvee labour to get their own money and to have village people doing farm work for them. All these different levels of taxation and corruption greatly inflated the amount of taxes people had to pay each year. Many of the poorer Hmong could not pay, and there are stories of some having to sell or pawn children to richer Hmong to borrow money for their tax obligations. Due to this financial burden, the Hmong had to increase their opium cultivation as the only means to get money to pay for their family needs and their taxes. Even those who previously did not grow opium now had to do it.

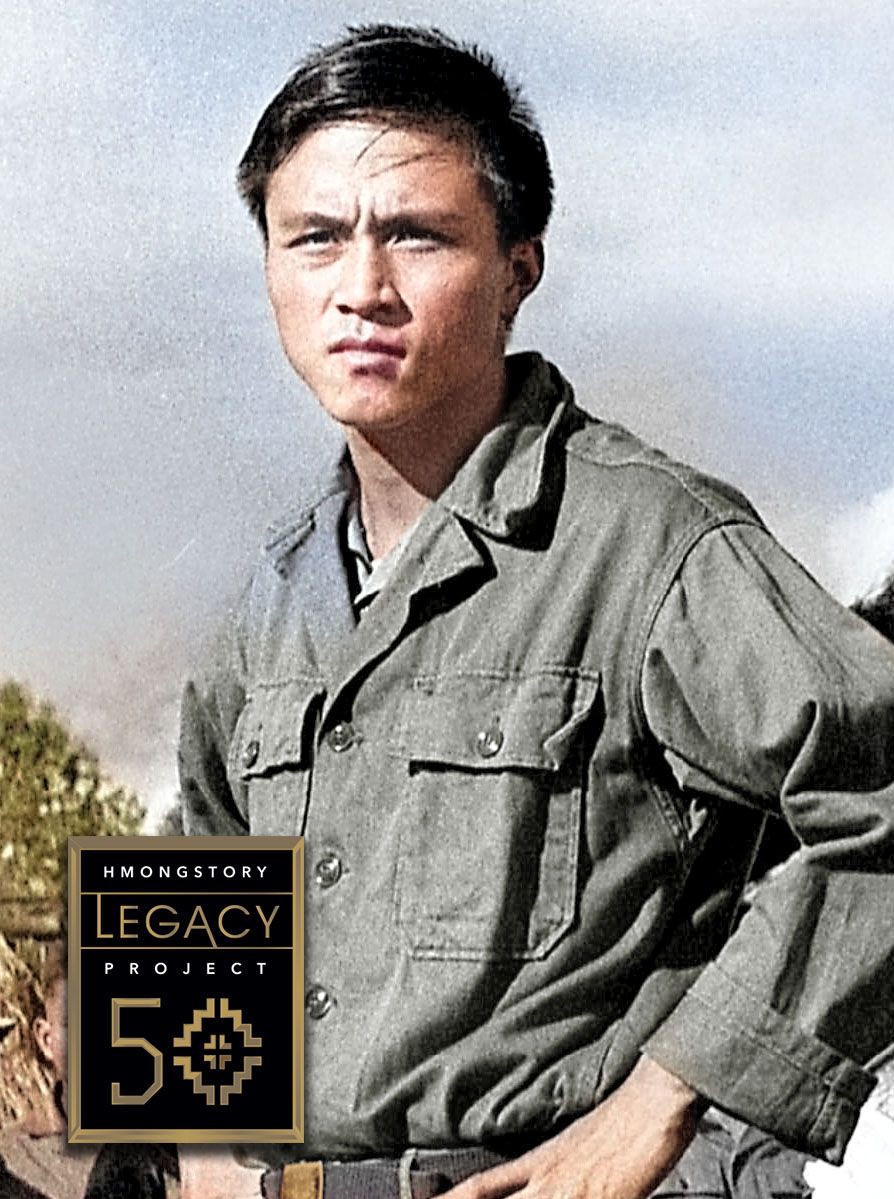

The impact of this severe official taxation is that the Hmong rose up in rebellion known as RogVwm or “Mad Men’s War” under the leadership of Pachay Vue (Paj Cai Vwj). Aided by Hmong messianic beliefs, the rebellion lasted from 1918 to 1921 – starting first in Vietnam and quickly spreading to all of northern Laos. The French had to bring colonial troops from other parts of Indochina to put it down. Today, Pachay is still celebrated by the Hmong of Laos and Vietnam as a revolutionary hero.

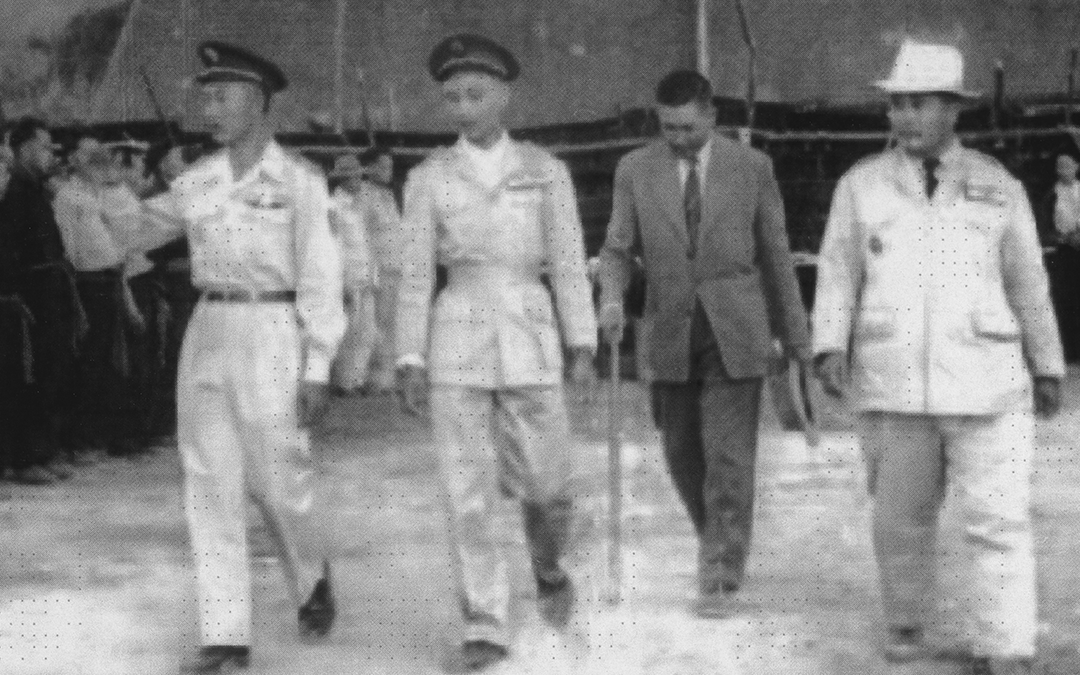

In 1947, the first Hmong deputy elected from Xieng Khouang to the Lao National Assembly in Vientiane, Mr Toulia Lyfoung, lobbied against this head tax and it was abolished, thus finally releasing the Hmong and other Lao citizens of this heavy burden.

HOW THE POPPY IS GROWN

In the traditional Hmong economy, no family would grow only one kind of crop as this would not meet all the family’s needs. Rice grows best in lower altitudes, so rice fields are often located lower down the mountain slope, away from maize and poppy fields. If a family grows all three major crops, then rice, maize and opium would be integrated into the annual farming cycle. Each family would give equal attention to them, although, the labor requirement may differ from one crop to another. Rice and opium has been found to need the same labor intensity (about 220 mandays per hectare), with maize about one two thirds less (80 mandays/hectare).

Maize (or corn) and poppy usually share the same field as both are suited for the same soil, altitude and weather conditions, with maize being grown first. All fields are worked by hands as they are often too steep and growers have no machinery to use. The scheduling of labour for each crop depends on the weather and how many workers are available. Maize fields (teb pob kws) are cleared (luaj teb) in January and February, followed by burning (hlawv teb) in March. Maize planting (cog pob kws) takes place in April, and weeding (dob nroj) in May.

The first corn cobs are harvested (ntais pob kws) in June-July, and by September all harvesting should be completed. August sees the preparation of the maize fields for poppy growing, starting with hoeing (faus teb yeeb) – turning up every inch of the soil manually with a hoe (hlau) and burying the dry maize stalks and weeds under. Early sowing of the poppy seeds (tseb yeeb) begins in September and should finish by October, a time when the Hmong are also busy harvesting rice.

November and December are spent weeding (dob yeeb) the poppy seedlings and young plants, a time when the Hmong also celebrate the New Year. Using a three-bladed small knife (riam yeeb), workers will tap the opium pods (hlais yeeb) and collect their sap (sau yeeb) with a scraping blade (duav yeeb) in January and February. Once collected, the sap (yeeb nyoos) from all the tappings is put together in a small container and allowed to dry. The year’s harvest is then wrapped in bamboo papers to be stored for safe-keeping and sale. The process completes with growers collecting poppy seeds (muab noob yeeb) in March to be used for the following year, and the next cycle of cultivation starts all over once more.

D. Feingold, “Opium and Politics in Laos”, in N. S. Adams and A. W. McCoy eds. Laos: War and Revolution (NY: Harper Colophon Books, 1970), p. 329.

Although they grow the drug, less than 10% of the Hmong are addicted to opium,. See J. Westermeyer,

“Use of Alcohol and Opium by the Meo of Laos”, American Journal of Psychiatry, 1971, 127 (8), p.1021.

G. Evans, A Short History of Laos, the Land in Between (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2002), p. 46.

M. Stuart-Fox, A History of Laos (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 32